Perspectives essay: making the case for a people-centred approach to sustainability in Greater Manchester

The Greater Manchester voluntary sector

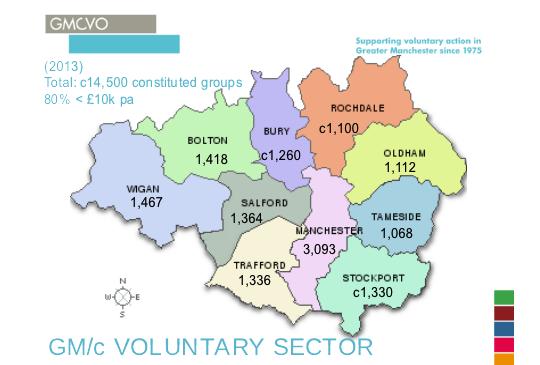

We are very fortunate in Greater Manchester in hosting an exceptionally large and diverse voluntary sector which adds considerable economic and social value to the city region. This comprises over 14,500 constituted organisations, and has well co-ordinated internal communications systems, at local and city-regional levels. In 2013 it employed about 23,600 people, plus over 334,000 volunteers giving 1.1million hours per week. The sector contributed 1.7billion to the Greater Manchester economy (3.5%). The medium-to-large organisations tend to rely on public or independent funders, as trading and enterprise are, as yet, less developed. However, around 82% of the groups have an annual income of less than £10,000, whilst more than three-quarters attract non-public sector funding (see http://www.gmcvo.org.uk/greater-manchester-state-voluntary-sector-2013). Under the radar of all this is a further layer of informal community groups - perhaps three times as many again. Much of the sector therefore comprises small, specific, volunteer-led groups, and is relatively resilient and autonomous. It both depends on, and generates, strong relationships between individuals usually with community of place and/or interest.

April 2011 was expected to be a watershed for the voluntary sector, and this would have been the case in a normal economic climate. As it was, an ongoing flat economy and savage public spending cuts made 2011-12 even more difficult than expected. The situation continues to have a very negative and unsettling impact on the local voluntary sector; uncertainty about grants and contracts persisted until autumn 2011 and recommenced in autumn 2012. As predicted, we have since started to see closures and reductions of voluntary services and, in some cases, of organisations. A survey by Greater Manchester Centre for Voluntary Organisations (GMCVO), conducted in early 2012 to look at the impact of changes in the voluntary sector on people and communities, showed that 56% had cut services themselves since April 2011 and 70% knew of other organisations which had done so; 73% reported increased demand for their remaining services but only 42% were able to meet this demand and only 32% hoped to continue to do so, whilst 54% were aware of new needs emerging. We remain extremely concerned about the welfare of those people and communities who were already facing inequalities of wealth, health, skills and quality of life and who are reliant on these services.

These difficulties were at least predicted, and the Greater Manchester voluntary sector as a whole may survive it better than most. But amongst people involved in local voluntary action, there is a sense that we now face a crisis of a more profound kind – a crisis of identity and morality. The boundaries between “public”, “private” and “voluntary” sectors are becoming more blurred and the relationships between them are being renegotiated. New resources on the horizon come with a price that many existing organisations may feel compromises their mission or presents unacceptable risk. New kinds of organisations are already evolving, but innovation is constrained not only by resources but by skills and structures.

A shared vision for sustainability

Given the wider context, both global and national, sustainability will not necessarily mean preserving existing systems, ambitions or ideas. If Greater Manchester is to be a sustainable city in future it needs to embrace radical change. Sustainability can mean different things to different people and groups, and can be considered from many angles. From my perspective, I consider that developing and agreeing shared values, principles and relationships are the bedrock on which to build a sustainable Greater Manchester. But I do not think we yet have adequate clarity and agreement about which values, principles and relationships will be most important to us as a city community.

We have had considerable debate within the voluntary sector over the last couple of years about values, triggered by the sense of crisis referred to above. All organisations have values, whether explicit or not. We have wondered whether there are any general values common to local voluntary action. If so, based on discussions and comments to date, I think the voluntary sector probably prioritises respect and tolerance of difference; compassion and help for those who are less well off; and an obligation to speak truth to power. Its operating ethos is based on self-help, trust and mutualism, treating individuals as whole people and working “bottom up”.

So sustainability is about people and our relationships with each other and our environment, about a good quality of life in a broad sense, not just about the economy – which would be seen as but one means to this higher end.

The Greater Manchester Strategy is an inspiring document, but in my opinion its vision of “prosperity for all” is unattainable if it continues to be predicated on economic growth as the sole indicator of worth without acknowledging quality of life; on inward investment as the main economic driver; and on the assumption that, regardless of whether they are the best ways of organising ourselves for the future, we will maintain existing organisations, institutions and systems. The delivery of the Strategy is also hamstrung by national government economic and social policy, which in practice gives us little freedom to set city-region priorities. Although some of these constraints are now being slightly lifted, I don’t yet see any radical rebalancing of power between the centre and the regional cities.

Currently we face a situation in which at least two of the three traditional sectors are effectively in fire-fighting mode, and a further government spending review (cut) will impact in 2015. We are witnessing the erosion of established networks and relationships as individuals are made redundant, and remaining employees attempt to cover their responsibilities. It is particularly difficult for people to stand back and reflect on what future sustainability might look like. Many ordinary people are disengaged from formal politics, and it is unclear to what extent everyone is “bought in” to what we may think of as society; episodes like the 2012 riots and the racial conflicts of a few years back, may just be the more visible symptoms of ongoing disengagement and frustration.

The inequalities of wealth, health, skills and quality of life referred to above are not new to Greater Manchester, although over the last few months we have also seen a frightening rise in poverty, with food banks and homelessness organisations experiencing expontential increases of demand. As with all the northern regional cities, some inequalities can trace their roots to the decline of heavy industry and working class communities; others reflect rural decline (see “On the Edge” GMCVO 2007 http://www.gmcvo.org.uk/node/1518 ); others are associated with the general disadvantage faced by black and minority ethnic communities and disabled populations, both of which are over-represented. What is clear is that the combined efforts over many years of the public and voluntary sectors, regeneration programmes and private sector growth have not yet succeeded in reducing these inequalities.

Key challenges therefore include an ongoing lack of autonomy as a city, which, amongst other things, hinders attempts to address systemic inequalities. But I believe the biggest challenge is conceptual, and that we cannot create a sustainable Greater Manchester without more agreement about what this means.

Unless all citizens are involved in developing a vision based on their own real aspirations and incorporating their own ideas and solutions, it is unlikely to be supported. Practically, of course, this could not be interpreted to require meaningful consultation with individuals on the details of policy. But the evolution and negotiation of the values and principles that might underpin a sustainability strategy, whether economic, environmental, cultural or social, cannot be done behind closed doors by a small number of people, even if they have a formal political mandate. It has to be “bottom up”.

The value of the voluntary sector

Everything I have seen of local voluntary action leads me to believe that there is some serious learning to be gained from the people involved. A more significant role for the voluntary sector and a wider adoption of some voluntary sector values would not in itself create sustainability, but could be an essential part of the solution.

For example, one of our major issues is worklessness, resulting not merely from a lack of jobs and stagnant micro-economies but from poor or irrelevant skills, non work-readiness and/or a cultural attitude which may go back more than one generation. This costs the city a great deal, directly and indirectly, and cannot be ideal for the individuals or communities affected. Many of the people least likely to enter the labour market are also disengaged from “normal” structures and pathways, so would not, for example, voluntarily visit a Job Centre or attend a college course. Yet many of these people are connected with or known to local voluntary groups and have trusting relationships with them. In 2006, GMCVO delivered a contract for the Learning and Skills Council aimed at addressing the worklessness needs of some specific groups least likely to become employed, such as people over 50, disabled people, lone parents, people from BME backgrounds. The “Towpath” project contracted with 67 local voluntary groups (mainly smaller ones) in touch with the right people, to bring them closer to employability; there were some very hard outcomes for a percentage of people to enter employment and formal learning, and softer outcomes on work-readiness and skills gaps. We helped 1,200 people (double the target), and achieved all hard and soft outcomes – at a cost of around £500 per person (referred to in “Building Social Marketplaces” GMCVO 2011 http://www.gmcvo.org.uk/building-social-marketplaces )

Another example - a group of voluntary organisations especially important to sustainability are community hubs / community anchors, of which we have a number in Greater Manchester. These are locality based, operating at neighbourhood level and serving all sections of the community with meeting space, resources, organised activities, public services and, in some cases, enterprise development. An example would be The Mosses in Bury, or Levenshume Inspire in Manchester. They greatly enhance community resilience and quality of life. But the great importance of these to sustainability is that they are massive generators of social capital in all three forms, enabling people with common bonds to come together, mix and form relationships with others, and connect with sources of knowledge, power and resources. Unfortunately, the enterprising activity of most of our hubs is not well developed and they are currently at risk from public spending cuts.

A final example is an alternative approach to food poverty which we have been developing in Rochdale with a partnership including the local authority, housing trust, CVS, community hub, Oxfam, the Co-operative Group and local “green” and food-based voluntary groups. The project is intended to take place in East Central Rochdale where Kashmiri and white populations face each other over a fertile patch of land. The Kashmiri community cooks healthy food, but much food is imported; the white community tends not to cook healthy food. The intention is to involve both communities in growing and cooking more of their own food using an asset-based community development approach (see http://www.abcdinstitute.org/). This should create environmental and economic sustainability alongside social capital, and should have many other benefits, such as public health outcomes.

What is needed now

I think the obvious big gap emerging is between formal city strategy and the ambitions and concerns of ordinary people, especially those who experience the worst inequalities. The Greater Manchester Poverty Commission (http://www.povertymanchester.org) published its findings in 2012, based on evidence as to why people find themselves in poverty and why they are unable or unwilling to escape it. I believe it is important that the answers are listened to carefully – but this is just a taster. There is, as far as I know, very little understanding of what ordinary people actually value and aspire to for themselves, their children or their communities, or what they would be most and least prepared to do to achieve their aspirations. We have only teasing examples like those mentioned above. The “social norm” is a mutual-dependency culture between public services, welfare and the individual, with policies and solutions driven from the top down; this is enhanced and structurally entrenched through national government and a culture of central control.

Again focusing down on the voluntary / community perspective, there is some useful emerging evidence from organisations like Urban Forum and Centre for Local Economic Strategies (CLES) about the factors which make a local community “resilient”, which is very relevant, including a recent study carried out in Cheetham Hill.

Besides understanding more fully what might comprise a shared vision of a sustainable city, we need much more knowledge about culture change and how to challenge destructive or obsolete social norms more effectively - we know enough to appreciate that culture change is slow and organic and cannot be imposed, but not enough about what catalysts, rewards and sanctions could support it.

Finally we need to look internationally at cities which have done better than we have at addressing one or more elements of sustainability, and see whether it is possible to use any of their ideas and approaches in Greater Manchester.

Success for me, and for many of my voluntary sector colleagues, would not be a long way from the vision described in the Greater Manchester Strategy. We would probably disagree with some of the proposals on how to get there.

The voluntary sector view would therefore probably be that sustainability success would look like a much fairer distribution of knowledge, power and resources leading to reduced inequalities; a greater reliance on well-resourced and well-mandated local voluntary action and community enterprise enabling people and communities to be treated as assets and solutions, rather than needs and problems; and an increased emphasis on quality of life and “social capital” and on the natural and cultural world, as being the things that most people actually value and which enable them to lead fulfilled and worthwhile lives.

Within the voluntary sector we do understand the crucial importance of the economy, and the role of our big private sector companies in generating wealth and creating employment through large-scale enterprise. As a sector, however, we have more in common, with regard to our operational models and our community roots, with small enterprises. Small enterprises, whether “for profit” or “non-profit”, continue to generate the majority of GVA (Gross Value Added) for Greater Manchester; but there are whole communities in which there is little enterprise and few jobs, and therefore little money circulating to make starting an enterprise a viable option. A rebalancing of the Greater Manchester economy through significant investment in the local “real economy” (whether “for profit” or “non-profit”) - encouraging people to make and grow things and to provide services for each other, retaining the local pound and building strong local relationships, would be a good step forward.

The questions of what we mean by sustainability and how to achieve it are perhaps the most important ones around. A first step would be to have a great deal more discussion, at every possible level and with every possible interested party. It would then be easier to begin to formulate those common values and principles, establish structural relationships, and grasp what the implications could be for Greater Manchester as a city region, for its people and for its institutions.

This Perspectives Essay was written as part of the Greater Manchester Local Interaction Platform's (GM LIP) 'Mapping the Urban Knowledge Arena' project. It was first written in August 2012 and last updated in July 2013. The GMLIP is one of five global platforms of Mistra Urban Futures, a centre committed to more sustainable urban pathways in cities. All views belong to the author/s alone.

Contributor Profile

Alex is the Chief Executive of Greater Manchester Centre for Voluntary Organisation (GMCVO), the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector support organisation for the Greater Manchester city region www.gmcvo.org.uk @AlexWhinnom