Perspectives essay: love food and hate waste

Summary

This perspectives essay focuses on sustainability in relation to food because it is a cross cutting issue which affects everyone and has a significant impact, locally at a Greater Manchester level and also globally. Food is important for the environmental, economic, health and well being of residents but there is a danger that it can get lost because there is no single organisation that co-ordinates food policy. Nevertheless, the total Carbon Footprint (TCF) of Greater Manchester clearly shows that food plays a significant part in residents’ carbon emissions. As 19% of our TCF is associated with food it is vital that there is a more coordinated, systematic approach to food policy and sustainable practice in Greater Manchester. Food Futures has an overview in Manchester and is working in partnership with a wide range of stakeholders. However, given the city’s location in the centre of Greater Manchester, access to significant areas of land to grow food is limited. Consequently a GM level food strategy with measureable outcomes/targets to address the challenges outlined in this essay is essential. Mapping of local food webs across GM would inform a strategic plan to address the issues of access to food and its supply and enable measurement of progress year on year.

This essay has been written collaboratively by Dr Debbie Ellen (independent researcher) with EMERGE's CEO, Lucy Danger. EMERGE is a long standing East Manchester based environmental charity which specialises in resource efficiency and aims to contribute to the creation of more resilient individuals and communities.

‘What do we mean by sustainability, in Greater Manchester?’

One of the simplest definitions is the Brundtland Commission’s, which defined sustainable development as that which "meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (United Nations, 1987, p.15). The Brundtland definition implicitly argues for the rights of future generations to raw materials and vital ecosystem services to be taken into account in decision making. This definition sums up EMERGE 3Rs approach to resource management in its broadest sense.

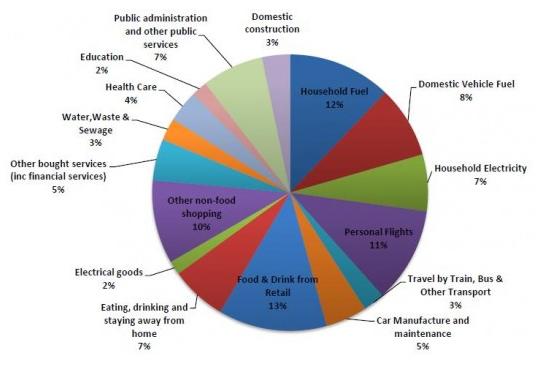

For this essay we will focus on sustainability in relation to food because it is a cross cutting issue which affects everyone and has a significant impact both locally and at a Greater Manchester level. Food is important for the environmental, economic, health and well being of residents but there is a danger that it can get lost because there is no single organisation that co-ordinates food policy. Yet the Total Carbon Footprint (TCF) of Greater Manchester (Small World Consulting, 2011) clearly shows that food plays a significant part in residents carbon emissions. Figure 1 below shows how a resident’s carbon footprint is divided up.

Figure 1: The greenhouse gas footprint of Greater Manchester residents broken down by consumption category (1).

As 19% of our TCF is associated to food it is vital that there is a more co-ordinated approach to food policy in Greater Manchester. Food Futures has an overview in Manchester and is working in partnership with a wide range of stakeholders. However, given the city’s location in the centre of Greater Manchester, access to significant areas of land to grow food are limited. Consequently a GM level strategy with measureable outcomes/targets to address the challenges outlined here is essential.

At the GM level currently food seems to fall within the remit of the Environment and Health Commissions – but is not very visible. Looking at the Environment Commission’s web page:

“Greater Manchester’s Environment Commission started work in 2009 with 19 board members co-ordinating with partner organisations to tackle climate change, energy, water, green infrastructure, transport, waste and other issues.

Our vision is to move Greater Manchester from red brick to green brick; to build on our former industrial heritage to a future that is ever greener and cleaner” (2).

Relocalisation of food supply, which is discussed below, will lead to a local food economy which can play an important part in the Low Carbon Economic Area. Consequently food growing must be prioritised in relation to development of the built environment. In Brighton the Local Authority has a Food Growing and Development planning advice note (PAN06) which provides guidance and basic technical considerations on how food growing can be incorporated into development, as part of the Council’s commitment to sustainable development (3).

A look at the GM Health Commission’s web pages also suggests that food is falling through the cracks, because it is a cross cutting issue. The themes identified for the Greater Manchester Health Commission for 2010/11 (4) are listed below;

- Alcohol

- Teenage pregnancy

- Public Protection

- Healthy Weight and physical activity

- Fuel poverty

- Mental Health and Wellbeing

- Health and the environment, spatial planning and transport

- Early Years

- Health Commission Task & Finish Group

- Cancer and Tobacco

- City Region Policy Evaluation

A healthy, sustainable diet links to many of these areas, but information available online around the contribution of food is very limited. Given the essay’s focus on sustainable food, we will outline what we mean by this term and what the key challenges are.

Definitions of Sustainable Food

Looking at local community based definitions of sustainable food FeedingManchester’s (5) early meetings brought together a range of practitioners, producers and activists to develop a definition of sustainable food with Greater Manchester in mind. Based on the Sustain (6) definition, it has 8 inter-related principles:

1) Local and seasonal

2) Organic and sustainable farming

3) Limiting foods of animal origin and maximising animal welfare standards

4) Excludes fish specifies identified as at risk

5) Fair trade certified products

6) Promote health and well being

7) Food democracy

8) Reduction of waste and packaging

The key challenges associated with sustainable food in Greater Manchester relate firstly to relocalising Greater Manchester’s food supply. A PhD study showed that the GM region scored particularly badly against a series of measures which looked at access to locally grown food. (Ricketts Heins, 2005) These measures are shown in Table 1 below.

| Table 1. Indicators of food relocalisation (7) |

| Number of local food directories |

| Number of local food producers advertising in local food directories |

| Number of organic farmers and growers licensed with the Soil Association |

| Number of farm shops selling food items registered with the Farm Retail Association |

| Number of Women’s Institute cooperative markets |

| Number of farmers’ markets |

Note: Each indicator is measured in terms of numbers per county.

Using this index Greater Manchester ranked 59th out of 61 counties. The most advanced in terms of localised food supply were found in the South West, and South East. This picture is not surprising, given the largely urban geography of Greater Manchester. What it does demonstrate is that action is needed in Greater Manchester to address food security and to build greater resilience to climate change by producing more food locally.

The second key challenge is the levels of deprivation in many parts of Greater Manchester, the importance of a healthy, sustainable diet on people’s health and wellbeing alongside low income levels. Linked to this the third challenge; perceptions of the cost of food, a lack of knowledge about how to prepare affordable, healthy meals from scratch. Whilst these issues are not unique to Greater Manchester, the pockets of deprivation across the area do mean that addressing the need for greater food security which will bring a greater resilience to the impact of climate change on food supply is a significant challenge. The 2012 growing season demonstrates the importance of increasing the amount of food grown in communities. Farmers are under pressure from large supermarkets to bare the cost of Buy One Get One Free offers. Poor harvests due to wet, cool weather in the UK and drought elsewhere in the world are having a knock on effect on food prices (8). One way to address the increasing cost of food is to provide people with knowledge about how to eat seasonally with food grown locally, and to prepare meals with less meat. Across Greater Manchester public procurement can lead the way in purchasing sustainable food and through initiatives like Meat Free Monday can regularly demonstrate the possibilities for eating a less meat intensive, lower carbon diet.

This essay will look at 3 examples of innovative approaches to the challenges of addressing sustainable food supply within an urban setting.

Mapping Local Food Webs

As part of the lottery funded Making Local Food Work programme, the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England embarked on an ambitious project to map 18 local food webs across England (9). This work provided detailed information about local supply chains and the contribution these ‘webs’ made to the local economy. A toolkit is being developed by CPRE to enable mapping of food webs. This will be an important tool to enable communities to use a tried and tested methodology for measuring the extent to which their food is local. Measurement of this kind is vital because it is important to know what already exists.

What constitutes a Local Food Web and local food?

CPRE defined:

“a local food web as the network of links between people who buy, sell, produce and supply food in an area. The people, businesses, towns, villages and countryside in the web depend on each other “

“local food as raw food, or lightly processed food (such as cheese, sausages, pies and baked goods) and its main ingredients, grown or produced within 30 miles of where it was bought. For all locations, outlets were in a core study area of a 2.5-mile radius circle centred on a town or city. Producers based within a 30-mile supply zone beyond this were counted as local.” (CPRE, 2012, p.2)

Looking at this definition it becomes apparent how challenging it is to look at the issue of local food in an area such as Greater Manchester, which has multiple towns and cities from which to apply a 2.5 mile radius circle. It would be possible to decide which towns/cities to focus on in order to establish a more localised picture of food webs across Greater Manchester than that done for the whole county by Ricketts-Heins (2005).

Another important aspect of food web mapping in Greater Manchester would be to compare availability and markets in deprived communities, where there are ‘food deserts’, areas where there is limited or no choice for food shopping (10).

Growing Communities’ Food Zones

Growing Communities is a community-led organisation based in Hackney, North London, which is providing an alternative to the prevailing food system, which it argues is not fit for the climate change and resource depletion challenges that lie ahead. Since its inception Growing Communities has created two community-led trading outlets - an organic fruit and vegetable box scheme and the Stoke Newington Farmers' Market.

“These [initiatives] harness the collective buying power of our community and direct it towards those farmers who are producing food in a sustainable way - allowing those small-scale farmers and producers whom we believe are the basis of a sustainable agriculture system to thrive. Growing Communities believes that if we are to create the sustainable re-localised food systems that will see us through the challenges ahead, we need to work together with communities and farmers to take our food system back from the supermarkets and agribusiness.” (11)

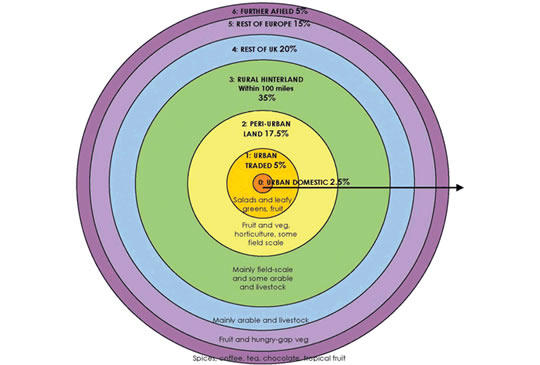

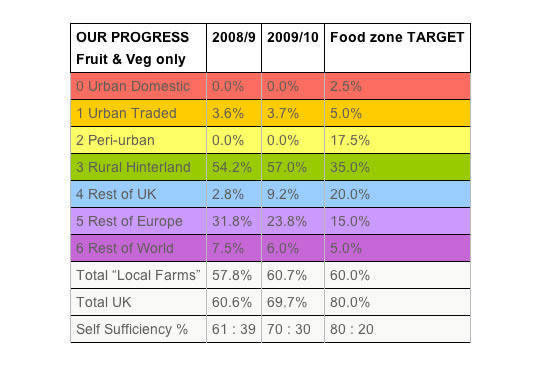

One of the key principles of Growing Communities is their commitment to source as much as possible from as locally as possible. They set targets for this and monitor where their fruit and vegetables come from based on a food zone model, reproduced in Figure 2 below. As with the CPRE mapping, the Growing Communities Food Zones cannot be used at a Greater Manchester wide level, because of the size of the GM area. However, each metropolitan borough could establish a zone, perhaps. The overall objective is to produce as much food as locally as possible and to have targets to work towards reducing dependency on food imported from Europe and further afield.

| Factors |

|---|

Moving from the inner to the outer zones:

|

One way this is achieved, which is being replicated by BITE in Manchester (see below) is by developing a ‘patchwork farm’ which has similarities to Viljoen’s continuous productive urban landscapes (2005). Small plots of land are identified and crops that have a high value and do not travel well without refrigeration are grown as locally as possible (e.g. salad and herbs). This model also takes inspiration from decades of experience in Cuba of growing enough food in urban settings to feed the local population (Viljoen and Howe, 2005).

BITE Veg Bag

In 2010 Growing Communities announced a start up scheme to enable other organisations to establish community led box schemes, using the successful model developed by Growing Communities. One of these organisations is BITE (12). With assistance and mentoring support from Growing Communities the BITE Veg Bag scheme was established in June 2011. BITE works with mental health service users to grow, process, pack and deliver veg bags to a range of community pick up points. Service users grow food at a number of allotment sites across the Manchester and aim to increase the amount of food grown by service users as the scheme develops. The veg bags are packed in North Manchester and taken to the pick up points for collection by customers (13). The Growing Communities model that is the basis for the social enterprise could be replicated across Greater Manchester.

EMERGE Food

Based in the heart of East Manchester’s regeneration area on New Smithfield Market EMERGE Food is part of EMERGE 3Rs, an environmental charity with over 15 years experience of empowering individuals, businesses and commuunities to reduce, reuse and recycle. EMERGE Food promotes the ideas and practices of healthy and sustainable food and procurement, engendering personal and environmental well being and the prevention of food waste. EMERGE Food operates FareShare North West, redistributing unwanted surplus food (in-date edible products) from the food industry. This ‘hub’ acts as a distribution depot where volunteers sort the food into smaller quantities and redistribute it to Community Food Members (CFMs) who are appropriately equipped and qualified to provide meals and food stuffs to disadvantaged individuals (e.g. homeless, drug dependent, low income, elderly, schools in deprived areas etc).

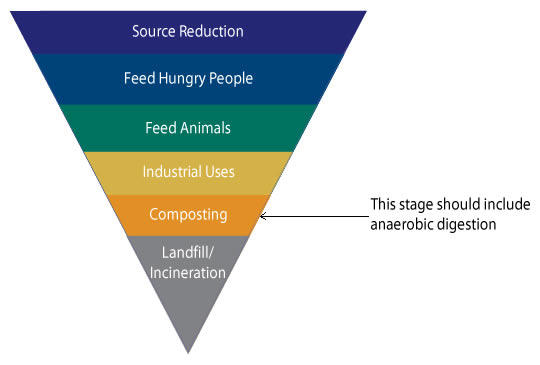

Since December 2011, in partnership with Manchester Markets and Food Futures, FareShare NW has been capturing fresh fruit and vegetables from New Smithfield Market wholesalers which would otherwise have been composted. This additional capture and redistribution of avoidable food waste addresses key principles of the food waste hierarchy (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3 Food Waste Hierarchy

In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (14) has developed a hierarchy for food waste (15) similar to the waste hierarchy used for other resource management. The advantage of this is that it clearly distinguishes between food that has no use for people or animals (to eat) – which should then be recycled – and food that is being wasted because of a range of structural problems along the supply chain. In the long term these structural problems must be addressed (as with fish quotas and throw backs). Kerry McCarthy, MP recently blogged:

“To put it very bluntly: obscene amounts of perfectly good food is being wasted, and there are good environmental reasons (avoiding landfill, promoting sustainable farming rather than production on an industrial scale, cutting emissions - at present 10% of rich countries’ greenhouse gas emissions come from growing food that is never eaten) and social reasons (tackling the ever growing problem of food poverty) to act.” (16)

In the short term is it important to look at ways to decrease the amount of edible food that is currently not being eaten. Since collection of avoidable food waste from NSM traders began over 11 tonnes of fruit and vegetables have been distributed through FareShare NW to CFMs. A long term objective is to establish a processing kitchen on NSM to maximise the amount of fresh avoidable food waste that can be used, by cooking surplus on site after CFMs have been offered food. Along side this EMERGE Food seeks to develop a network of local food champions to offer cookery sessions both at NSM and in community venues across North, East Manchester and Wythenshawe enabling people to learn how to cook affordable healthy meals with fresh ingredients. This will build on work done for Greater Manchester Waste Disposal Authority (GMWDA) promoting Love Food Hate Waste in 2010 by delivering demonstration workshops in communities.

Gaps in Knowledge

A key gap in knowledge relates to measurement. It is very difficult to get a picture of what is currently happening (amount of food produced where, number of community growing projects, community cafés, cookery sessions, impact of diet on health outcomes etc.) at a GM level and outcomes from all such activity. How then do we measure progress or address gaps in provision when delivery of work is largely through time limited projects, many of which may not have ‘sustainability’ or ‘climate change’ as their focus?

The definition of sustainable food outlined above points to the need to address changes in consumer behaviour. However, as Thøgersen (2010, p. 171) states:

“When discussing the problem of unsustainable consumption, there is a perhaps natural tendency to focus on individual consumers’ decision making and behavior. However, it has been convincingly argued that the attitudes, preferences, and choices of individual consumers are less important for the sustainability of private consumption than are the macro and structural conditions that frame and constrain individual choices”

Thøgersen focuses on one area of the sustainable food debate: organic food, comparing EU countries. He reviews research across Europe concluding that macro and structural conditions, determined by policy and market actors, play a key role for the level of organic (and therefore also sustainable) consumption in a country. Across Europe one structural condition that impacts on all producers is EU regulation of the size, shape and colour of fruit and vegetables (18). Naturally occurring products that do not run off a production line are subjected to quality control measures more appropriate to a factory than food. This has an impact along the supply chain, increasing the cost of production because farmers are not able to sell food that fails to meet the grading criteria. Smaller farmers are less able to process or sell on graded out food, which leads to on- farm avoidable food waste. Data about the scale of this is not available (in the UK at least), which makes addressing this structural issue very difficult.

Returning to the role of the consumer, research has shown that while many people are aware that changes need to be made there is a significant gap between this knowledge and action (Thøgersen, 2005). It is well known that elements of a sustainable diet are also important from a health perspective, for example, eating less meat. In more deprived communities across Greater Manchester the structural issues can be profound: the range of shops to buy food from may be very limited, people may lack the skills to cook using raw ingredients, or the equipment to cook with. In this setting community cafés and community growing projects have a key role to play, as food brings people together. By looking at ways to share knowledge about how to grow and cook food, as EMERGE aspires to, the emphasis can be taken away from the individual consumer. Community growing projects can cook and preserve food grown locally to feed local people. As the BITE Veg Bag scheme expands (both growing and selling food) they hope to supply community cafés in just this way.

Conclusion

Food is a key area of sustainability in Greater Manchester because it accounts for 19% of residents TCF. As a cross cutting issue food is falling through the cracks in terms of strategy and policy which needs to be addressed. Mapping of local food webs across GM could inform a strategic plan to address the issues of access to food and its supply and enable measurement of progress year on year.

Public procurement policy can play a major role in developing a local food economy across Greater Manchester, which would in turn provide a reliable market for local growers. In conjunction with that one simple step which would have a significant impact would be for all GM Local Authorities to roll out Meat Free Monday across their catering operations, providing low carbon, healthy, nutritious food to both demonstrate a commitment to sustainable food and show how recipes can be reproduced in the home. Further national or GM level funding of successful campaigns such as Love Food Hate Waste, which work with organisations in communities offer a ready made means of discussing these issues with GM residents. Through these cost effective routes Greater Manchester can achieve a great deal to address the contribution of food to residents Total Carbon Footprint.

Inline References

1 The Total Carbon Footprint of Greater Manchester. Estimates of the Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Consumption by Greater Manchester Residents and Industries (Small World Consulting August 2011). See Downloads Below.

2 www.agma.gov.uk/commissions1/environment_commission/index.html

3 PAN06 - The advice will apply to new commercial, residential and mixed developments and is the result of collaboration between the City Council Planning department and Food Matters, as part of Harvest Brighton and Hove, a lottery funded project which supports more food growing in the city. See Downloads Below

4 www.greatermanchesterhealth.org.uk/work-plan/

5 www.feedingmanchester.org.uk/

6 Sustain is the alliance for better food and farming. See www.sustainweb.org/sustainablefood/

7 Taken from Ricketts Heins et al., 2006, p.292

8 Recent news stories include: www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/aug/12/farmers-wilt-under-supermarket-promotions?INTCMP=SRCH; www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-19209693; www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-19188333;

9 Reports for each local food web are downloadable from: http://www.cpre.org.uk/resources/farming-and-food/local-foods

10 The CPRE project mapped Burnley’s food web, but this report has not yet been published (expected 2013).

11 http://www.growingcommunities.org/about-us/

12 A partnership initiative of Manchester Mind and Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust.

13 Since this essay was written the BITE Veg Bag has ceased training. It remains a relevant example of a local food initiative with environmental, social and economic benefits within communities.

14 www.epa.gov/waste/conserve/foodwaste/

15 A similar ‘pyramid’ has been developed by Tristam Stuart in collaboration with Feeding the 5000, the Mayor’s Waste Strategy team, the London Food Board, Recycle for London, Friends of the Earth, WRAP, FareShare & FoodCycle. See www.feeding5k.org/businesses.php

16 www.kerrymccarthy.wordpress.com/2012/03/12/what-a-waste/ accessed 30/7/2012.

17 www.growingcommunities.org/start-ups/what-is-gc/manifesto-feeding-cities/explore-food-zones/

18 EC Marketing Standards for Fresh Horticultural Produce (Reg. 543-2001) available online: eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:157:FULL:EN:PDF

References

Association of Greater Manchester Authorities (2012) Environment Commission web Page Online at: http://www.agma.gov.uk/commissions1/environment_commission/index.html, accessed 26 July 2012.

BBC News web site. (2012). Bad weather set to increase bread price. Online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-19209693, accessed August 14 2012.

CPRE, 2012. From field to fork: The value of England’s local food webs. Campaign for the Protection of Rural England, London. Available online at: http://www.cpre.org.uk/resources/farming-and-food/local-foods/item/2897-from-field-to-fork , accessed 26 July 2012.

European Commission (2011) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 543/2011 of 7 June 2011 laying down detailed rules for the application of Council Regulation (EC) No 1234/2007 in respect of the fruit and vegetables and processed fruit and vegetables sectors

Online at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/JOHtml.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:157:SOM:EN:HTML.

Food Matters/Harvest Brighton & Hove (2011) Planning Advice Note 6 Food Growing and Development, written with support from Brighton and Hove City Council. Online at:

http://www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/downloads/bhcc/ldf/PAN6-Food_Growing_and_development-latest-Sept2011.pdf, accessed 16 July 2012.

Greater Manchester Health Commission (2012) Workplan (web page). http://www.greatermanchesterhealth.org.uk/work-plan/,accessed 26 July 2012.

Growing Communities (2012) Growing Communities’ Food Zones: Towards a sustainable and resilient food & farming system Online at: http://www.growingcommunities.org/start-ups/what-is-gc/manifesto-feeding-cities/explore-food-zones/ , accessed 26 July 2012.

Insley, J. (2012). British farmers wilting as supermarkets pile on the promotions The Observer. Online at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2012/aug/12/farmers-wilt-under-supermarket-promotions?INTCMP=SRCH, accessed August 14, 2012.

Mardell, M. (2012). US crops tell story of future world food prices. BBC News Online at: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-19188333, accessed August 14 2012.

Ricketts Hein, J., 2005. Culture, identity and the re-localisation of food supply in England and Wales. PhD thesis, University of Coventry.

Ricketts Hein, J., Ilbery, B., Kneafsey, M., 2006. Distribution of local food activity in England and Wales: An index of food relocalization. Regional Studies 40, p. 289–301.

Small World Consulting . 2011 The Total Carbon Footprint of Greater Manchester. Estimates of the Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Consumption by Greater Manchester Residents and Industries. Online at: http://manchesterismyplanet.com/_file/t1CdrX8LUv_110758.pdf accessed 25 August 2011.

Sustain (2012) 7 principles of sustainable food. Online at http://www.sustainweb.org/sustainablefood/, accessed 26 July 2012.

Thøgersen, J., 2005. How may consumer policy empower consumers for sustainable lifestyles? Journal of Consumer Policy 28, p. 143–177.

Thøgersen, J., 2010. Country Differences in Sustainable Consumption: The Case of Organic Food. Journal of Macromarketing 30, p. 171–185.

United Nations, 1987. Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. United Nations, Geneva.

Viljoen, A. (Ed.), 2005. Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes: Designing Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Cities. Architectural Press.

Viljoen, A., Howe, J., 2005. Cuba: Laboratory for Urban Agriculture, In: Viljoen, A. (Ed.), Continuous Productive Urban Landscapes: Designing Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Cities. Architectural Press, p. 146–191.

This Perspectives Essay was written as part of the Greater Manchester Local Interaction Platform's (GM LIP) 'Mapping the Urban Knowledge Arena' project. The GMLIP is one of five global platforms of Mistra Urban Futures, a centre committed to more sustainable urban pathways in cities. All views belong to the author/s alone.