Sustainable spotlight on Manchester International Festival

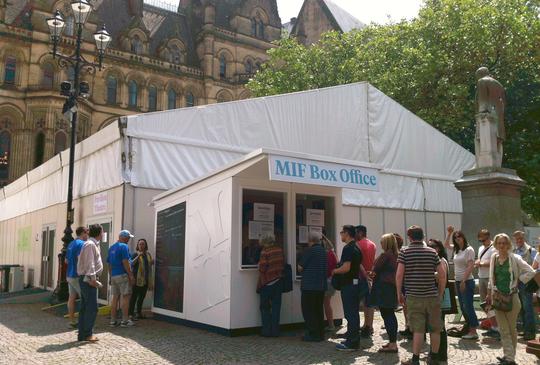

Manchester International Festival (MIF) is the world’s first festival of original, new work and special events and takes place biennially in Manchester, UK. The Festival launched in 2007 as an artist-led, commissioning festival presenting new works from across the spectrum of performing arts, visual arts and popular culture. In this article, drawing on interviews with different members of the MIF team, Beth Perry highlights their less well popularized but equally important role in contributing to Greater Manchester’s environmental sustainability.

MIF prides itself on having made a significant commitment to reducing the environmental impacts of its office operations and was the first festival to be independently certified as meeting the sustainable events standard, BS8901, as well as a recipient of A Greener Festival award. Whilst the ethos of being artist-led is central to their mission, benefitting the local economy, engaging local communities and minimizing its environmental impact are also stated core principles. Examples of activities have included: greening the office space; sourcing and creating productions responsibly and working with partner venues to reduce the environmental impact of MIF events.

Greening the Office Space

Like other cultural organizations, the growth of the environmental sustainability agenda within MIF started with small-scale changes. Efforts were invested in minimizing the environmental impact of the MIF offices through purchasing energy efficient machines, improving office practices around recycling and re-use, and reducing the use of paper, or, where necessary using FSC accredited paper stock. Other activities included purchasing ethical products and fair trade tea. A Green Team manages the environmental targets of the Festival, which are the result of internal policies rather than external pressures. The UK Arts Council’s sustainability targets are, for instance, a recent development. Staff are incentivized to adopt green travel incentives – through being able to reclaim bike travel at a rate of 20p per mile.

With strong support from the upper echelons of the organization, supported by good networks, the Festival enrolled to take part in the trial for the BS8901 standard for event sustainability. A strong synergy between environmental and cultural values was critical to the birth of the sustainability agenda: “We are a Festival of premieres, we kind of premiered the BS8901, and it fits with what we all believe in", said Gemma Saunders, MIF's Green Team Co-ordinator.

The Green Team agrees on targets, specifically for transport, waste and communication. MIF consists of a core team of 16-20 people, expanding during the Festival years and each department is represented in the Green Team. MIF now has an international standard for sustainable events management (ISO2012). Whilst this represents emerging good practice in the sector, such standards can be full of jargon and difficult to achieve.“This is a big tome of work", said Jennifer Cleary, MIF Creative Learning Director, "and it is noted that it is not particularly accessible to smaller organizations that do not have the kind of resources that MIF have” (2012).

Assessing the Impact of the Festival

Festivals, of course, don’t usually take place in offices. They are spread out into places across the city-region, in formal cultural venues, on the street, in squares, in meanwhile spaces, in reclaimed industrial mills. Alongside improvements in the office, it quickly became apparent that MIF needed to consider its venues as well: “We go into found spaces that don’t have anything in them, electricity, water - so we have to come up with ways of doing, ways of getting those things in - and we think about those in sustainable ways” (Gemma Saunders, 2013).

We calculate the carbon for the office we don’t do the festival because, who has the capacity to calculate carbon for an entire festival? (Gemma Saunders, 2013)

The team realized that it was very difficult to monitor and reduce the carbon footprint of a festival, given the varied spaces into which it reaches: “We calculate the carbon for the office we don’t do the festival because, who has the capacity to calculate carbon for an entire festival?” (ibid)

One space over which MIF does have control is Festival Square. In 2011, actions included using compostable cutlery and tableware and expanding recycling facilities which saved 79% of festival waste from landfill. Partnerships with the City Council were developed to secure electricity supply without the use of external generators, bikes were used to help staff get around, production sets were re-used and recycled and banners upcycled into usable bags.

The priorities for 2013 linked in with the themes of transport, waste and communication. The team developed targets for the amount of waste going from Festival Square to landfill, achieving an impressive 1% of waste going to landfill with help from Enterprise, waste management. They sought to promote their sustainable ethos through a programme of awareness-raising. Since 2009, this has included attaching the sustainability policy to all contracts for artists. Walking routes were clearly marked in the brochure and online and hybrid cars were procured from Electricity North West to move Festival artists around, a development made possible also due to the introduction of electric charging points in NCP car parks. Even the mud didn’t go to waste, with the residues from the Macbeth production going to local allotments.

Sustainability in Cultural Programming?

With a remit to engage creative audiences with the ‘urgent stories’ of our time, the environmental agenda has been central to the development of the Festival and is manifest, not only in the office space, but also within cultural programming. In 2009 MIF commissioned the Manchester Report to get leading thinkers to come up with radical, experimental revolutionary ideas about how to reduce climate change emissions. This was a partnership with the Guardian newspaper and involved inviting high-profile thinkers to present their ideas to a panel of experts, chaired by Lord Bingham, in front of a live audience.

Although MIF does not specifically set out to produce an ‘environmental commission’ each year, 2013 also saw a cultural ecological collaboration between the Biospheric Foundation and MIF to produce the Biospheric Project. Stemming in part from MIF’s previous efforts to construct a vertical farm in 2011, the final project built on the Biospheric Foundation’s 30 year vision to achieve a transformation in the urban ecological systems in the city. Through the 18 month collaboration, MIF supported the Biospheric Foundation to develop the emerging urban farm/urban research laboratory and engaged with the public around issues such as food culture, community growing and urban forestry.

Attracted to the deep community embeddedness of the Biospheric Foundation and the long-term vision, the collaboration has played an important part in what is conceived as a much broader transition. As Vincent Walsh, Director of the Biospheric Foundation noted (2014): “They helped me massively… helping me structure, getting the right people in, helping with volunteers and all that kind of stuff - our team on our own wouldn’t have been able to do it.” After the 18 day Festival ended, the challenge for the Biospheric Foundation is now to create a 10-year business plan – “The hard work now begins…I’ve invited them to join the Board as I’d like to continue a longer term relationship with the Festival to protect the investment that was made there” (Vincent Walsh, 2014).

A long-term journey

Organizational support has been a key factor in achieving successes to date. Like Cornerhouse, the Festival’s staff refer to a natural synergy between environmental and cultural dispositions, ensuring that efforts to embed sustainability can be focused on external engagements, rather than internal persuasion. The urban context has also played its role, making progress easier to achieve over time. In the space of just two years, the operating conditions in Manchester changed dramatically: “In 2009 when we said to the caterers ‘we only want you to use compostable packaging’, it was a proper battle. It was so expensive and we couldn’t share the cost. We had to get someone to collect it and Greater Manchester didn’t do regular food collections at that point. We managed because we found a bloke who just was willing to experiment with us and saved a whole container in his plant that was just our waste in case it was contaminated. It worked really well and in the end the waste was composted and spread over farmers’ fields within two months. Two years later …people had started doing it kind of closer to home and now Enterprise does it all and we have managed to get to the 1%, which is amazing, because of how they do it at their plant (Gemma Saunders, 2013).”

Examples like this point to the challenge of measuring impact. Many of the targets and performance indicators selected by the Green Team are difficult to measure in terms of numbers or quantifiable metrics. This is particularly the case given the specific challenges that cultural festivals have in accessing, managing and monitoring different spaces in the city. Whilst organizations such as Manchester Art Gallery can manage their own building, experimenting with cooling and heating, MIF owns neither the urban spaces it uses, nor indeed the office: “We are not in control of this office space because we rent it from Bruntwood - so we can’t decide who our electricity supplier is, or whether we have got magic taps - but Bruntwood are really helpful and they have got a really good sustainability agenda. They helped certify us ISO2012 (ibid)”.

A difficulty facing the Festival is the high level of transport required. As an international festival, the team recognize that importing over a thousand extra people into the city for 18 days creates transport chaos: “it’s absolutely an enormous problem…some artists just don’t want to cycle round on a bicycle” (ibid). Consequently, in some years, the Festival has experimented with off-setting, putting money towards solar roofs in Wythenshawe, but is currently looking into the scientific calculations behind offsetting to evaluate their approach. Like the academic world, the Festival hits against the demands of a globalizing world in tension with sustainable local behaviours: “We have introduced more technology… but there are certain things that we can’t change because of the fundamentals of what we are doing. We want people to come here from all over the world as well (ibid).”

The Festival hits against the demands of a globalizing world in tension with sustainable local behaviours.

These issues sit behind MIF’s central role in catalyzing the Manchester Arts and Sustainability Team (MAST). MIF were central in developing relationships between cultural organizations interested in sustainability and drawing in Julie’s Bicycle to offer support to the development of Manchester Cultural Leaders Environmental Forum (MCLEF) before it developed into MAST in 2012/2013. “It’s good that people are communicating with each other and that MIF is represented and not forgotten in the year and a half that we are not really around that much” (Gemma Saunders, 2013). Since late 2013 MIF have chaired the MAST group, working closely with other organizations such as Cornerhouse and Band on the Wall.

An Alternative?

The Manchester International Festival is unashamedly, first and foremost, an international artistic event. In this, it appears highly successful. Its impact on the city can also be seen in economic terms through, for instance, the growing popularity of Manchester as a tourist and cultural destination. For some people in the city, it’s all good: the bourgeois buzz, the excitement, the transformation of the city into a cultural hive, the opportunity to participate in innovative new works, delivered on the doorstep. For others, perhaps those unable to afford the tickets despite the reduced prices for residents, they may recall the swelling visitor numbers, the increase in traffic or a sense of invasion by cultural elites. So much is placed on those 18 days that it is perhaps understandable that other cultural organizations in the city, particularly those with fewer resources or political clout, may feel crowded out.

But this is not a Festival that only engages with the city for 18 days a year. Bringing new collaborative, voluntary partnerships together such as MAST, supporting sustainable event management and commissioning cultural ecological projects as art, all illustrate that MIF has a sense of belonging to the city-region. MAST represents an emergent collective consciousness and leadership of the cultural sustainability agenda, represented also in the commitment of MIF to commission works which deliver on artistic integrity, whilst capturing the stories of our time.

This suggests that a future role for the Festival, particularly given the massive disparities in arts funding per head between the North and the South of the country, may be to provide a mentoring role in relation to smaller cultural or community initiatives to enable them to learn from MIF’s experiences.

The Festival is large, one of Manchester City Council’s selected strategic investments, and has a privileged position in the cultural mainstream in the city. There are multiple other cultural initiatives in the city and outside it which suggest a more alternative or radical rethinking of the relationship between art and ecology, a sub-cultural ecology that does not benefit from the resources or reputation of MIF. This suggests that a future role for the Festival, particularly given the massive disparities in arts funding per head between the North and the South of the country, may be to provide a mentoring role in relation to smaller cultural or community initiatives to enable them to learn from MIF’s experiences.

But ‘can Festivals ever be green?’ Mark Briggs, in the Ecologist, argues that audience travel accounts for the greatest part of the carbon emissions. Co2penhagen in Denmark, an arts and music festival, was heralded as the world’s first CO2 neutral festival (http:www.co2penhagen.com). Its website makes great claims about the local sourcing of all energy using renewable sources. Yet the small-print notes that whilst they can ensure carbon neutrality for the three days of their festival, they cannot ensure this in the preparation phase, in relation to transportation or with food and drinks that are delivered and sold. In carbon terms, these are pretty significant omissions. To that extent, it could be argued that festivals can only ever tinker at the edges of actual carbon reduction. The real opportunity is through public engagement with the festival going audience.

The real opportunity is through public engagement with the festival going audience.

MIF have started along this long road, exploring alternative energy generation, dealing with waste and raising the profile of critical environmental issues. Through the environmental agenda, there is already evidence that the Festival is using its position to bring about broader change. It contributes a central part of the picture of how the city-region needs to transition to a more sustainable future and is highly visible within the city’s cultural landscape and ecology. To that extent its catalytic role, combined with a more collaborative ethos, suggests an alternative sense of responsibility that needs to be cultivated from large-scale public events, so they are both in and also for our cities.

Further information

http://www.mif.co.uk/

http://www.mif.co.uk/about-us/green-mif/

http://www.biosphericfoundation.com/

http://www.mif.co.uk/gallery/the-impact-of-the-biospheric-project

http://www.co2penhagen.com/?page_id=69

@MIFestival

@BF_UK_CIC

Sources:

*Interviews with Gemma Saunders, Jennifer Cleary and Vincent Walsh.

*‘Can Festivals ever be green?’, Mark Briggs, http://www.theecologist.org/green_green_living/out_and_about/1378954/can...

This article has been written as part of the ‘The Alternative?’ series by the Greater Manchester Local Interaction Platform for Mistra Urban Futures.

It also draws on work carried out for the Arts and Humanities Research Council ‘Cultural Intermediation’ project. It is part of a working paper in development for publication on Low Carbon Culture? as part of the Mistra Urban Futures research agenda.

Image Credit: Monika Lukasik

Contributor Profile

I am a Professorial Fellow in the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Sheffield. I describe myself as an interdisciplinary urbanist, interested in processes of transformation and change, particularly around governance and policy processes; the roles of universities in their urban environments; and the research-practice relationship.